To celebrate Seed Savers Exchange's 50th anniversary, we are featuring the work and inspiration of Exchange listers in the "Hope and Practice" series.

Hope and Practice: Christina Wenger

‘The best way to keep a historic variety alive is to grow and share it.’

Christina Wenger, Exchange lister, recounts why she grows, saves, and shares one particular sweet pea variety.

In the first third of the 20th century, the agricultural valleys of California were full of sweet peas grown for seed, and even though Morse (of Ferry-Morse) grew his seeds a little further south on the peninsula, he maintained his business in San Francisco. This very land where my house now stands used to be covered in greenhouses for flower production. Maybe, in the early 20th century, like in other parts of California, sweet peas grew plentifully here. And perhaps, in the spring, the whole hill was fragrant with flowers. I like to picture it so.

Whether or not sweet peas grew here in the past, they grow here now. But the single variety that I choose to grow dates back to 1904, so it could have been here 100 years ago.

Sweet peas are among my favorite cut flowers to grow, especially the old varieties that were bred as much for fragrance as for other characteristics. Modern sweet peas have relatively large, ruffly flowers, with many per stem. But, so often, they lack the scent that gives them their name. Older varieties may or may not be ruffly (depending on whether they are pre or post the development of ruffly ‘Spencer’ varieties), but they’re dependably fragrant. However, it’s getting harder and harder to find single-named heritage varieties in the United States. Seed companies occasionally sell heirloom mixes, but only a few sources provide named heritage varieties.

The best way to keep a historic variety alive is to grow it and share it. That’s how another seed saver and I kept afloat a breadseed poppy that enslaved people grew at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. When I first received seeds for that plant from Seed Savers Exchange member Patrick Holland, he included this letter:

“These seeds come from the poppy original [sic] grown by Thomas Jefferson on his estate in Virginia called ‘Monticello.’ I first obtained this seed from a member some years back who, herself, obtained it from Monticello. For some years now, the operators of the estate have discontinued its sale. For approximately five years, as far as I know, I am one of the only persons (or the only) who possesses this seed. It represents an unbroken chain of seed transmission that extends back for over 200 years. No one should be burdened with bearing that responsibility alone. [. . .] As of this year, there will be only four people left with this seed, including yourself as one of them. That’s 200 years of living history in four [sic] hands.”

I grew these poppies and shared the seed through the Exchange and my local community, and I bragged about the plants’ beauty until it was picked up by fellow gardeners, then by Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, and now a few other commercial sources, too. The sources have renamed the variety to ‘Charlottesville Old,’ but it is the same plant. Holland’s effort of maintaining the plant and sharing the seeds with me, and then the both of us sharing it and telling other people about it means now lots of people have access to its beauty when it had been almost extinct.

So, since named heirloom sweet peas are harder and harder to find in the United States, and because this general area of the country was once a hotbed of sweet pea happiness, I decided to adopt a variety: ‘Henry Eckford.’

I chose this variety because it is a bold red-orange, and I love orange things. It’s just a slice more orange than runner bean blossoms, but a lot more red than the color of orange fruits. I chose this variety because it is ridiculously fragrant, so much so that I can smell it in my whole garden when it blooms. And I also chose it because the “father of sweet peas,” Henry Eckford, felt so connected to this variety that he named it after himself. Eckford released this variety in 1904, so it appears to be one of the last varieties that he developed before he died in 1905.

I also chose it because there is something about Eckford’s story that appeals to me. He started out, like many plant people do, by working for other plant geeks before ending up in charge of other plant geeks. He had a two-decade-long gig at an estate as a head gardener. But he still hadn’t started developing sweet peas. He didn’t start his sweet pea experiments until after his first wife died in childbirth, he remarried, and he left a long-held and stable job. He didn’t start sweet peas until his world shifted entirely, and he took a job I wonder if he had ever previously imagined:

“In 1878, Eckford was invited to work in the gardens of the lunatic asylum at Sandywell Park, near Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, run by the physician William Henry Octavius Sankey (1814–89). Sankey was a keen amateur hybridist himself, and together they raised seedlings of florist’s flowers at Sandywell and then, from 1882, at Boreatton Park, Shropshire, where Sankey moved his asylum.” (Urquhart)

According to Urquhart, Eckford began his exploration of sweet peas in 1879. He started the sweet pea developments for which he became famous while he worked with and for a doctor at the “lunatic asylum.” There is so much more I want to know about that story.

Eckford’s variety ‘Bronze Prince’ was the first to catch the attention of the garden world of the time, and for it, he won a Royal Horticulture Society award in 1882. ‘Bronze Prince’ has disappeared through time and history. There aren’t even any images of it, according to a blog on The Gardens Trust website titled The Sweet Pea and Its King. By its name alone, ‘Bronze Prince’ sounds like a flower I wish I could have met.

I didn’t get to meet ‘Bronze Prince,’ but I am lucky to know Henry Eckford’s self-named variety. I think I might also know a little something about the man from the plant he chose to name after himself. It’s a loud, funny color. It gets sunburned easily. For a sweet pea, it is pretty darn tough, rolling with drought and brushing off the dreaded powdery mildew. It doesn’t hide its fragrance, and even though it works well in a vase all by itself, it gets along with others beautifully.

Sources:

Holland, Patrick. Personal letter. 27 March 2008.

“The Sweet Pea and Its King….” The Gardens Trust, 26 Sept. 2015.

Taylor, Judith. “Sweet Peas in California: A Fragrant but Fading Memory.” Pacific Horticulture. Accessed 30 June 2022.

Urquhart, Suki. “Eckford, Henry.” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H. C. G. Matthew et al., Oxford University Press, 2004, p. ref:odnb/96775. DOI.org (Crossref).

Christina Wegner of San Francisco, California, lives and gardens on the top of a hill on the sunny side of the city. She currently offers five varieties on the Exchange, including the ‘Henry Eckford’ sweet pea. She originally shared this article in July 2022 on her blog, A Thinking Stomach.

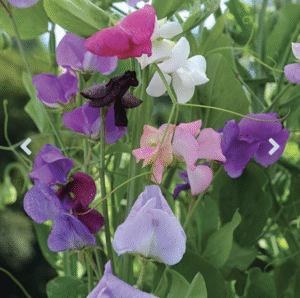

SSE has a sweet pea for you!

This mixture of strongly scented, historic sweet pea varieties includes bicolored and striped blossoms. Note: Sweet peas are poisonous.